Two fragments from 'Política británica en el Río de la Plata' (1940)

By Raúl Scalabrini Ortiz. Translated by me.

Gonna try to keep the obligatory intro-to-the-intro section short. Evidently, this is a translation. I explain from what and why I think it is important below.

I have a tendency, when writing here, to ramble a bit about my personal life in very oblique terms that are probably incomprehensible to anyone except my actual friends who read this (if even to them). Typically this is my way of making an excuse for not posting, since admittedly I do so infrequently. Enough of that. Less excuses, more content. My new motto for 2025.

Raúl Scalabrini Ortiz was one of the founders of the “revisionist” school of Argentine historiography, an extremely broad term which in its application essentially means any thinking that is remotely nationalist or left-wing. As such, he was particularly interested in the history of British “informal empire” in the River Plate as an explanation for Argentina’s underdevelopment and economic stagnation. A few things in the following passages that I think are of particular note:

-The illusory nature of Argentina’s “Golden Age” (late 19th, early 20th-century) prosperity. Scalabrini Ortiz (1940) continually highlights just how different Argentina was from the anglophone settler states — U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand — to which it is frequently compared. These laid a basis for continuous, balanced growth through the domestic ownership of major capital assets (e.g., railroads) and the access to private landholding of a large swathe of the population. Nothing of the kind occurred in Argentina, where arriving European immigrants were overwhelmingly relegated either to tenant sharecropping or to life in an urban slum (see Peña, 2012: 320-224; Scobie, 1964: 47-54). And where railroads, shipping, etc., were all British-owned (though the former, at least, were nationalized under Perón). To me, this calls into question the frequent, reflexive characterization of Argentina as a settler-colonial state — a settler definitionally, takes into ownership land stolen from an indigenous population. And this phenomenon is widespread enough to define an entire national society. How can someone be said to have stolen land that is not and was never in their possession? Settler-colonialism is intrinsically egalitarian — it promises everyone (that is, all whites) an equal chance to “make it” on the frontier. An oligarchy of the Argentine kind seems incompatible with settler society, and makes it more similar to any other in Latin America — societies rarely termed settler-colonial due to their mestizo- or Indigenous-majority populations. In this analysis I am still indebted to J. Sakai (2014).

-The absolute centrality of Argentina in the late British Empire. Not that it was as important as the “jewel in the crown,” India, of course — which supplied at gunpoint troops and financial surpluses in near-infinite quantities, allowing Britain to rule the world. Still, Argentina was no doubt key to the late British imperial ‘food regime,’ since its gigantic export surpluses kept prices for meat and grain low worldwide (see Friedmann and McMichael, 1989). This, in turn, prevented runaway inflation (allowing the pound sterling to continue exercising its reserve-currency function) and kept the British working class fed with a cheap and abundant diet. Before Americans were ever fat and ate burgers, Englishmen were fat and ate roast beef.

-There is an interesting description of unequal exchange at work. Scalabrini Ortiz notes that Argentina’s second-rank position as an agro-food commodity supplier to Britain (behind the United States) presents a misleading picture. Since trade statistics focus on the money value of exports rather than their simple material volume, the far lower prices paid to Argentina for its products leads to a systematic underestimation of how important this country is as a food exporter. Scalabrini Ortiz convincingly goes on to demonstrate that a huge share of the British consumption basket is supplied by Argentina, far more than its seemingly low share of trade value (7.23%) would indicate. I like this example because it is very concise, and should be of interest to trve Emmanuel nerds and fellow travelers alike. It also reinforces the above two points. Note further that the unequal exchange going on is in the first instance ecological — Britain lives beyond its means by and because of drawing on hundreds of millions of ultra-fertile Pampean acres, without having to shoulder the real costs of putting and keeping them in production. Trying to produce the equivalent amounts of beef, grain, etc. on British soil would require drastic land-use changes trading off with towns and industrial production, even leaving aside the dubious prospect of its being physically possible. Britain escapes the ecological limits of its island setting, not in a Ricardian mutually beneficial relationship with Argentina but rather at the latter’s expense. This comes in the form of soil exhaustion, and the displacement of traditional gaucho rural subsistence economies by the range being fenced-off or converted to cropland. Nor can the price differential be explained with reference to the quality of Argentine products. Beef in particular was produced with considerable attention to British consumer tastes. From the late 1880s-onward, the Sociedad Rural spearheaded a monumental effort to remake the nation’s bovine gene pool through selective breeding and the importation of new stock (described in Barsky and Gelman, 2009: 182-190; Scobie, 1964: 43-45). That the meat of animals with the resulting perfect marbling and tenderness still fetched less than generic beef on global markets is an indication that Ricardian trade theory is deeply flawed.

-The earlier point about inflation and the pound sterling was inspired by that power couple of agrarian Marxism, Prabhat and Utsa Patnaik (2016; 2021). Their concept of “income deflation” denotes forcing the population in peripheral agrarian-producing countries to consume less (via direct colonial coercion or more recently, contractionary fiscal policy) so that the export surplus is greater, and thus food commodities become cheaper on the worldwide market — it’s supply and demand bro. Scalabrini Ortiz’s data surprisingly bears this out for Argentina of all places, a society which is reputed to eat meat in huge quantities. During the 1930s, however, meat consumption was not all that great in Buenos Aires and the surrounding litoral provinces (which tend to be wealthier) and at levels which would have caused genuine malnutrition in the poorer interior. Note that this was the “Década Infame” (infamous decade) of ultraconservative authoritarian rule which followed the overthrow of Hipólito Yrigoyen. A period in which all labor action was met with intense violence, fascist-curious and antisemitic Liga Patriotic (Patriotic League) toughs roamed the streets, and wages were suppressed. Note moreover that this was coinciding with wartime demands on the British economy, which prompted the archetypal example of income deflation cited by the Patnaiks — the various policies in India which caused horrific famine in 1943. Note thirdly that under arch-liberal Javier Milei, Argentine meat consumption has once again plummeted — to the lowest level in 110 years.

-In general, the absolute contemporaneity of means of exercising power in the late British empire. We associate direct colonialism with Britain and Europe, and debt-trapping, propaganda, the cultivation of a subservient local media and ‘civil society,’ etc., with the United States. All of these and more, however, were pioneered by London, and used only afterwards by its rebellious former colony. To me, this calls to mind a very Arrighian (2010) dynamic where a rising hegemonic power is that which supplants the former one by being able to put its own tools and techniques of world-governance to better and more extensive use.

A final brief word on Scalabrini Ortiz. Política británica en el Río de la Plata translates to ‘British Policy in the River Plate.’ It is not his most famous work, that being Historia de Los Ferrocarriles Argentinos (‘History of the Argentine Railways’). Scalabrini Ortiz was initially a Radical (a supporter of Yrigoyen — today the Radicals are a largely irrelevant, center-right party), who later moved towards Trotskyism. The history of Argentine Trotskyism is fascinating, and very different from the preconceptions which some readers may have about Trotskyism coming from the United States or Britain (here, the Stalinists sided with imperialism!). I will hopefully write something about this in the future. The work of Scalabrini is somewhat polemic, and lacks both the incomparable erudition and the dry humor of fellow Trotskyist Milcíades Peña. It is also written in a dryer, more ‘academic’ Spanish, with much of Peña’s magnum opus being in lunfardo — what most people think of as Argentine Spanish today, featuring extensive borrowings from Italian (ex: che, laburar) and Brazilian Portuguese (mina). It is still arguably a more vulgar or ‘low’ dialect, but makes for a much more pleasurable reading experience. My own grandfather, when I told him about my new job over the phone, first chastised me for calling it a laburo before extending his congratulations. Of course, he comes from a time when lunfardo was still somewhat stigmatized as the language of slum dwellers.

I hope to do some translations from Peña soon.

References

Arrighi, Giovanni. The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times. [New updated ed.]. London: Verso, 2010.

Barsky, Osvaldo, and Jorge Gelman. Historia del agro argentino: desde la conquista hasta comienzos del siglo XXI. 3. ed. actualizada. Colección Historia argentina. Buenos Aires: Ed. Sudamericana, 2009.

Friedmann, Harriet, and Philip McMichael. "Agriculture and the state system." Sociologia ruralis 29, no. 2 (1989).

Patnaik, Utsa, and Prabhat Patnaik. A theory of imperialism. Columbia University Press, 2016.

Patnaik, Utsa, and Prabhat Patnaik. Capital and imperialism: Theory, history, and the present. Monthly Review Press, 2021.

Peña, Milcíades. Historia Del Pueblo Argentino: 1500-1955. C.A.B.A. [i.e. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires]: Emecé, 2012.

Sakai, J. Settlers: The mythology of the white proletariat from mayflower to modern. PM Press, 2014.

Scalabrini Ortiz, Raúl. Política Británica En El Rio de La Plata. 4a ed. Buenos Aires: Plus Ultra, 1965.

Scobie, James R. Revolution on the Pampas: A Social History of Argentine Wheat, 1860-1910. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1964.

p. 230-236:

… To contribute to English well-being, Argentina sends to the United Kingdom 40% of its exports of raw materials and foodstuffs. According to the official numbers, we are England’s second-greatest supplier. First place goes to the United States, whose exports were valued at £83 million in 1932. We contributed 7.23% of all English consumption. But this is a misleading statistic. It does not reflect the volume of merchandise and raw materials which we sent. And it does not reflect this because the price which England pays us is much lower than that which it pays to its other suppliers. Rather than considering the values, we will attend to the quantities. In 1933, Argentina exported to England:

-507,000 tons of cow and sheep meat

-42,847 tons of wool, [both] dirty and washed

-8,000 tons of butter

-12,388 tons of cowhides, dried and salted

-131,000 tons of oats

-129,164 tons of barley

-103,396 tons of flax

-2,312,119 tons of corn

-1,215,670 tons of wheat

-19,509 tons of flour

-195,525 tons of bran

-2,537 tons of sheepskins

-24,052 tons of quebracho [a type of tree] extract

-200,000 tons of miscellaneous commodities (30% of which were produced to order)

= 9,903,717 tons

The newspapers announce as an auspicious sign that our exports increased. The profits from that increase in exports serve, above all, to increase the gains of English capital invested in this country. The English people will eat more and their rentiers will profit more. We will soon return to the principal mechanism used by English finance to suction our wealth outwards. To steal it away from its rightful owners, and remit it to England.

In the face of such a prodigious volume of exported merchandise, a basic question comes to mind almost automatically. Is Argentine production capacity so great? Does the exported material constitute a real excess, a surplus left over after the needs of its own country are fulfilled? Or is this this food stolen from the populace, whose labor is thus wasted?

Let us establish some correlations which will orient us to the comparison between distinct types of diet.

Calculations per head have been scrupulously performed for both countries, England and Argentine. The overall levels of consumption have been taken from unimpeachable sources: “The Statesman’s Year Book, 1934.” “World of Facts, 1934,” section on England, the “Bulletins” of the General Directorate of Rural Statistics and Economy [of Argentina], and the Journal of Municipal Statistics insofar as it discusses Argentina. The data on median English consumption of meat, fish, and fruit has been taken from an official memo produced by Carlos Antonio Pardo, published by the General Consulate of Argentina, in London.

Annual meat consumption:

England . . . . . . . . 66 kgs. 720

Argentina . . . . . . 69 kgs. 800

Average meat consumption merits some commentary. The English average can be accepted as factual, given that consumption in London, according to statements by the manager of Smithfield Market, coincides approximately with this number.

But in Argentina the opposite is the case. The city of Buenos Aires has an extraordinary [per-capita] meat consumption of 130 kgs. 820, one of the highest in the world, possibly due to its use as a means of compensating for the scarcity of other foodstuffs. The average in the interior of the Republic, that is the average consumption level of 10,000,000 Argentines, is a mere 55kgs. 456, a grossly inadequate quantity because the relative scarcity of meat is not compensated for with any other form of nutrition. Some provinces are dying of hunger. Jujuy consumes 43.8 kgs.; La Rioja, 27 kgs.; Catamarca, 26 kgs., and Santiago del Estero just 19.6 kgs. These figures translate into anemia, decrepitude, the physical degeneration of several hundred thousand Argentines. We insist on this point with authoritative support. Let us continue to enumerate the consumption averages.

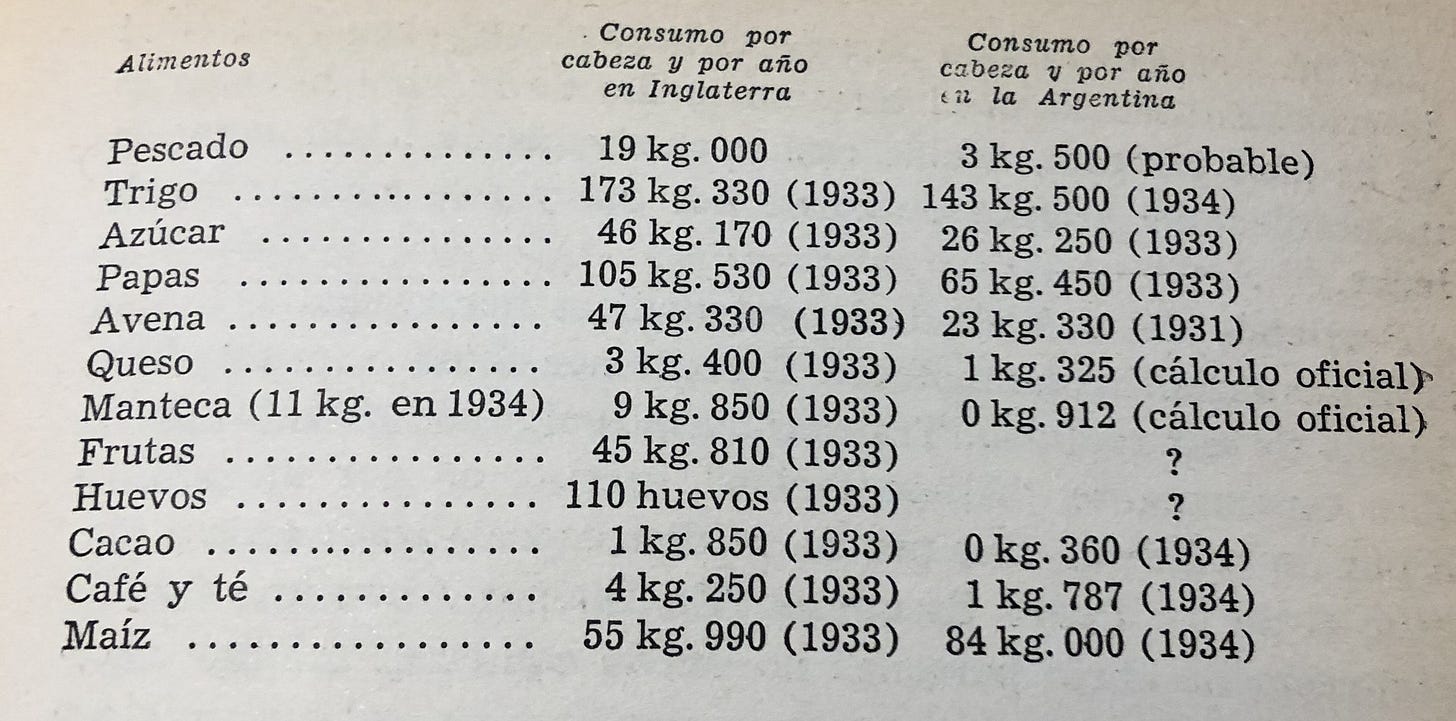

[Translator’s note: The following table is rather too complex to reproduce here in text form. The columns from left to right read “Foodstuffs” “Consumption by head, per year in England” and “Consumption by head, per year in Argentina.” The x-axis is a list of food commodities, from top to bottom: fish, wheat, sugar, potatoes, oats, cheese, butter, fruit, eggs, cocoa, coffee and tea, and corn.]

These figures already indicate the Argentine nutritional tragedy; the people of Argentina eat little and live poorly so that the English people can eat a lot and live well. The enervation of our energies, in order to fortify those of England, is immediately expressed by all observable key indices.

The average human lifespan in Buenos Aires is 38 years, 4 months. In London it is 53 years, 6 months. Official data. Or expressed in another way, demonstrating that the lower average in Buenos Aires is not due exclusively to high local infant mortality:

For every hundred people born:

On their nineteenth birthday, in London, 81 will still be alive, in Buenos Aires, 69.

On their twenty-ninth, in London, 77 are still alive, in Buenos Aires, 58.

On their thirty-ninth, in London, 72 are still alive, in Buenos Aires, 48.

On their forty-ninth, in London, 63 are still alive, in Buenos Aires, 36.

On their fifty-ninth, in London, 49 are still alive, in Buenos Aires, 25.

Average porteño life expectancy is very high in comparison to the interior. In San Juan the median lifespan is 24 years, 8 months, due almost entirely to a miserable diet: 100 grams of meat a day and 6 teaspoons of milk.

Proceeding from an analysis of the statistics we have discovered a lamentable Argentine reality. We turn now to a direct study of that reality. Here are transcribed a few paragraphs from a shocking book, “Diet,” written, not by a politician or a bureaucrat but rather medical professional who specializes in this subject, Dr. Pedro Escudero. “In Buenos Aires a family composed of five persons cannot feed itself sufficiently to survive on the basis of a five-peso salary. As the majority of the working masses do not earn even this, logically it can be inferred that they are unable to feed themselves in order to stay healthy and assure the conservation of the race.” (p. 166).

“What most clearly demonstrates the consequences of an inadequate diet on generations of Argentines is the study of their physical debility. Failure to meet height, body weight, and chest diameter requirements for military service indicate a physically degraded state in an individual and when the proportion of recruits unable to meet these standards reaches a certain level it signifies the degeneration of the race. Out of 426,944 Argentine 20 year-olds, 43,044 were classed as physically unfit to serve, which indicates that a full 10% of all conscripts in the country are unfit due to stunting.” (p. 181).

“From studying statistics compiled by the Military Health authority one obtains conclusions of indisputable proof-value. From them it can be deduced that 30% of all conscripts in the country are physically defective. Out of that enormous number of diseased, 34% present with signs of physical degeneration resulting from the malnutrition of their parents and grandparents.” (p. 188)

“Low salaries explain why malnutrition is the rule for more than a third of the population and also our biological characteristics, so inferior to those of the great civilized nations, the high level of infant mortality, the low average life expectancy in general, the lesser vigor of the native compared with the foreigner who lives among him, problems of a high percentage of which occur among men and women of reproductive age, are the consequence of an insufficient and incomplete diet.” (p. 267).

Contemplating this horrifying reality, Dr. Escudero engages in meditations which are very depressing. “The state of undernutrition in which the majority of Argentines live, is the dietary regime of slaves and has always been a means for strong men to dominate their fellows. No more effective dominating force is known than insufficient diet. The most vigorous organisms, the most rebellious spirits, and the most brilliant minds slowly and fatally are extinguished like a lamp which consumes all of its oil.” (p. 167).

“At some point,” he asks, “will there arise clear-minded, strong-willed Argentines who will comprehend this problem and resolve it?”

Having demonstrated that English salaries and wages, though they have declined 5% in nominal value, have increased their purchasing power by 11%, the situation of a class which is very numerous in England remains to be analyzed, that of rentiers in general, agrarian rentiers, rentiers of public funds and rentiers of foreign investments.

One good indicator of English opulence is the enormous consumption of alcoholic beverages, which increases year after year. According to calculations by the Alliance of the United Kingdom, in 1935, £237,732,000 was spent on alcohol, which is to say the fantastic sum of 4,041,444,000 pesos, or almost 100 pesos annually per head just on beverages. This spending in 1935 exceeded by £8,703,000 the numbers for 1934 (Telegram of “La Prensa,” 3 April 1936). But let us continue looking at the wider English statistical panorama.

English national income has undergone a 15% contraction, which is in no way comparable to that suffered by Argentina, whose national income collapsed by about 50%. Clark, in “The National Income,” estimates that the English national income suffered the following fluctuations: in 1929, it was £3,996 million, equivalent to 1,509 pesos per head per year. In 1930, it descended to £3,938 million; in 1931, £3,499 million and it fell to £3,380 million in 1932.

67% of this income consists of wages and salaries, whose recipients, as we have seen, have experienced a net improvement in their condition during this span of years. The remaining 33% of English national income is that which corresponds to the rentier class.

Let us study the three types indicated. We have demonstrated earlier, incontrovertibly, that the so-called English crisis is a ridiculous lie, constructed to trick gullible nations like our own.

English farmers have suffered no competition from our bargain-basement prices. Their cereal production is defended by a 10% ad valorem tariff and by a duty on our grain, exclusively, of 2 shillings per quintal (exactly: 2 shillings for 448 lbs.), which is to say approximately 8 pesos per ton. With this tariff on our wheat a fund is amassed which is partially returned to English farmers as a subsidy. In 1932 they received £4,197,000, which at the exchange rate of 17 pesos to the pound results in the enormous sum of 71,349,000 pesos. In 1934 the funds distributed increased to £5,342,000, meaning 80,797,000 pesos. This occurred in the same year that our government, via exchange-rate manipulation, stole 100 million pesos from our farmers and stock-breeders…

[Translator’s note: I have rendered the Spanish “Inglaterra” as “England” throughout, since that is literally what it means. It should be fairly obvious that Scalabrini Ortiz is using this as a metonymy for the United Kingdom as a whole.]

p. 263-268:

The destruction of the industrializing drive of a country does not have a simple economic or financial explanation. Strangling local industry is, effectively, a task whose fulfillment benefits the English balance of payments and provides the opportunity for super-profits. Delaying the industrialization of another country is a longtime British imperial policy. Norman Angell, author of the widely-circulated book “The Great Illusion,” today an imperial adviser, “Until 1860 the underlying principle of British policy was the fundamental idea that those governing England must impede the development of the United States.”

Such principles and such ideas continue to be applied shamelessly to the Republic of Argentina.

British policy in the Republic continues to be one of suffocation and domination. Its most venerable arm continues to be the railways, for which purpose they were constructed. Foreign-owned railways are an instrument of holding back progress, as is well explained by Allen Hutt in [his] The end of the crisis. Hutt says: “Railway construction in less-developed countries and in the colonies is not done in pursuit of the same goes as it is in England, which is to say — and this is essential — it is not part of an overall process of industrialization. These railways are built simple to open up those regions as sources of food and raw materials, vegetal as much as animal. Not in order to accelerate development by stimulating local industry. In reality, the construction of colonial railways and those in subordinated countries is a sign of imperialism, acting in the anti-progressive role which is its essence.” This policy has provoked, naturally, protests which are stifled by their own impotence.

The railway can unify a collectivity or be its most pernicious disassembler. Thus, the attitude of peoples who achieve national consciousness is to immediately obtain control over their national railway system. Bismarck consolidated the unification of Germany with the centralization of railway lines, imposed via expropriation. Italian unity was affirmed in the state appropriation of all railroads on the peninsula. The statesmen who initiated Japanese greatness also demonstrated comprehension of the basic foundation of an organic national unity, and, in spite of having more energy than means, they nationalized all railroads by expropriation (Law #7 of 31 March 1916).

So essential are the railways for the development of [an independent] commercial policy that not even in English colonies are the railways English-owned. The essential rail-lines in Canada are not English, they are Canadian. The Dominion government nationalized them in 1917 (7-8 Geo. V, c. 24). The Canadian state possesses in actual fact a first-order rail system, 38,548 kilometers in length. Data of the “Annuaire du Canada, 1932” (page 563).

Neither are the Australian railways English, they are Australian. Out of a total of 44,356 kilometers of track 39,356 pertain to the various states or provinces, 3,459 kilometers to the Commonwealth or central government, and only 1,496 kilometers are private property. “Year Book, 1934.”

In those countries where the railways remain under local control, legislation has been made strictly obligating them to serve, above all else, the national interest. The U.S. legislation is a particularly magnificent example of state intervention in the rail sector. Via its authorized powers, the government regulates fares, capital formation, safety of employees and the public, salaries, enterprise accounting, and the guidance of traffic flows. Five successive laws have steadily increased state control: The Act to Regulate Commerce of 1887; The Hepburn Act of 1906; The Man Elkins Act of 1910; The Federal Control Act of 1918; and The Transportation Act of 1920, or Esch-Cummings Act, which gave such far-reaching powers to the Interstate Commission that the United States government can be considered to effectively own the railways, in the public interest.

Our own neighbors can provide examples of prudent legislation with regards to railways. In his interesting Geografía Económica del Brasil, the great Argentine Jorge B. Crespo summarizes the history of Brazilian railways in the following terms: “The various acts of subterfuge employed by English railway companies obstructed the work of the enterprise’s comptroller, for which reason Congress opted for its nationalization and administration, as spelled out in the law of 9 December 1896.” The Brazilian railway concessions tendered prior to the law had to submit to regulations meant to safeguard the national interest, such as the obligation to have at least 80% of technical and administrative personnel consisting of native citizens, a requirement similar to that spelled out in Chilean law. Article 57 of the Ley General de Ferrocarilles de Chile states explicitly: “Concession-holders should maintain among their directorial, technical, and administrative staff a proportion of Chilean citizens not less than 75% of the total employed, for the full duration of their concession. It is prohibited to employ citizens who have not completed mandatory military service.”

For all our best efforts, we cannot find anything resembling the Argentine laws, except in those concessions which the Europeans have forced upon Asian nations, under the threat of violence and which resulted in the total submission of this continent and the dismemberment of venerable empires like that of China. In such cases European wishes faced no challenge other than those thrown up by the envy of rival powers. The importance of gaining control over railway concessions is brought into full relief by the intense competition which they awaken. When the Chinese government conceded to Great Britain the railway between Chang Hai Kuan and Liao Tung, the Russian government considered its interests in the Far East so seriously aggravated that the concession had to be annulled so that Great Britain and Russia could reach an agreement, the Treaty of 28 April 1899, in which Britain promised not to seek railway concessions north of the Great Wall in exchange for Russia agreeing not to do so in South China. In the struggle between Britain, Russia, France, and Germany, the possession of a railway was considered an instrument of the first order for dominating a sphere of influence; but in the Argentine Republic the railways were conceded to foreigners without restriction of any kind and the ultimate, most painful result is that the Republic is now nothing more than “an English sphere of influence now beginning to face the threat of penetration by the United States.” Little by little, we have become, without noticing it, a “virtual English colony,” according to the clinical analysis of J.F. Horrobin, whose Manual of Economic Geography has recently become popular in England.

The English railway has filled in the Argentine Republic the same subjugating role as in China, in Tonkin [Vietnam], in Persia, in Arabia, and in Afghanistan, and it is time that we stop to understand and profoundly meditate upon this national reality.

All Argentine progress in some way harms English hegemony. All Argentine industry displaces a similar English industry or that of [an English] satellite, whose products England uses to trade.

The jacket or shoe manufactured in Argentina, diminishes at a minimum the profits of an English textile mill, of a marine shipping line and of a railway. Imagine if some grand reserve of a metal is discovered and exploited [here], as a result of which thousands go to swell the legions of the parasitic unemployed, many blast furnaces are extinguished, and many cargo boats no longer have a purpose to sail. Keeping the deposit unmined would be, in such a case, the logical English policy, whether it be via taking possession [of the metal deposit] without actually exploiting it — as is the case with the borate deposits of the Gobernación de los Andes [Translator’s note: defunct Argentine territorial subdivision] — or via the elevation of transport rates so as to be prohibitive, as has long been done with the petroleum of the north.

The most powerful instrument of English hegemony among us is the railway. The weapon used by the railway is its rate. Transport rates play a significant role in the life of a nation. Using them it is possible to impede industries, create privileged areas, promote regional fragmentation, encourage cash-crop production, and even to destroy flourishing cities. It is an insidious weapon, silent, and frequently undetectable until one has already fallen victim.