Interpreting the AMIA V -- La Pista Siria

Menem, Croatia, Who (probably) did it, and Why that matters

Yeah, I was planning to leave this unfinished.

I’ve been very, very busy this spring with offline stuff, and most of my downtime has been spent working with Miroslav on the podcast (most of what will be covered below incidentally, is already the subject of Regime Radio E5 “The Boys From Yabrud,” which you can find here).

That’s not the main reason for dropping off with the AMIA series though. It’s more just that it seemed unnecessary to finish it. I just… stopped needing to shout into the void on Substack to get people interested in this insane event. After Chapo and getting a bit of an audience for our own show, it started to be that non-Argentine people who are smarter than me and have bigger platforms wanted to know about it.

Also, I’ve done some real-world academic work around AMIA since then, which, to be frank, has scratched my urge to write about it way better than Substack ever could.

But there’s a persistent question after you explain to people the entire story that has been told here up to now, which is “OK, so Iran didn’t do it. Who did?”

The catalyst to write this last entry was a news story last week, which was presented in Argentine media and in translation as the courts finally, definitively ruling that Iranian officials ordered the bombing. Actually, that isn’t quite what happened. First (confusing as this might be), the ruling wasn’t made in the actual AMIA case. Second, all that happened was a judge stating that he believed Iran was responsible for the attack, but this wasn’t the issue being tried and no new evidence regarding culpability was presented. In other words, very little that the Argentine state has not already said on multiple occasions.

And if we think that the government is — maliciously — wrong every time it reasserts this narrative, then what really happened?

In 1989, Argentina elected a president who was not what he seemed.

First, Carlos Saul Menem was in fact no suave, all-Argentine macho. He was the 5’5 first-generation son of Syrian immigrants whose performance of Europeanized masculinity — complete with Catholic conversion, Hispanicized name (from “Menahem” to “Menem”), River Plate allegiance, extensive plastic surgery, skin-lightening makeup, and heel inserts — was all for the cameras. His flamboyance, tackiness, and frivolity while doing so perhaps is what gave away the lie.

Second, Menem was no left-wing Peronist (a pose which, in fairness, he would drop in his second and third election campaigns). Upon entering office, his denunciations of American imperialism would be replaced by “carnal relations” with it; and his championing of the working-class would be replaced with dollarization, privatization, and consumerism for the rich (Aguiló, 2018: 28-34).

Third, he was not just the boss of a patronage machine in La Rioja. The truth was something less horrifying to the ruling elite — a warning sign — but much harder for the average person to understand. Menem was enmeshed in a sprawling web of international intrigue, war, diplomacy, and crime.

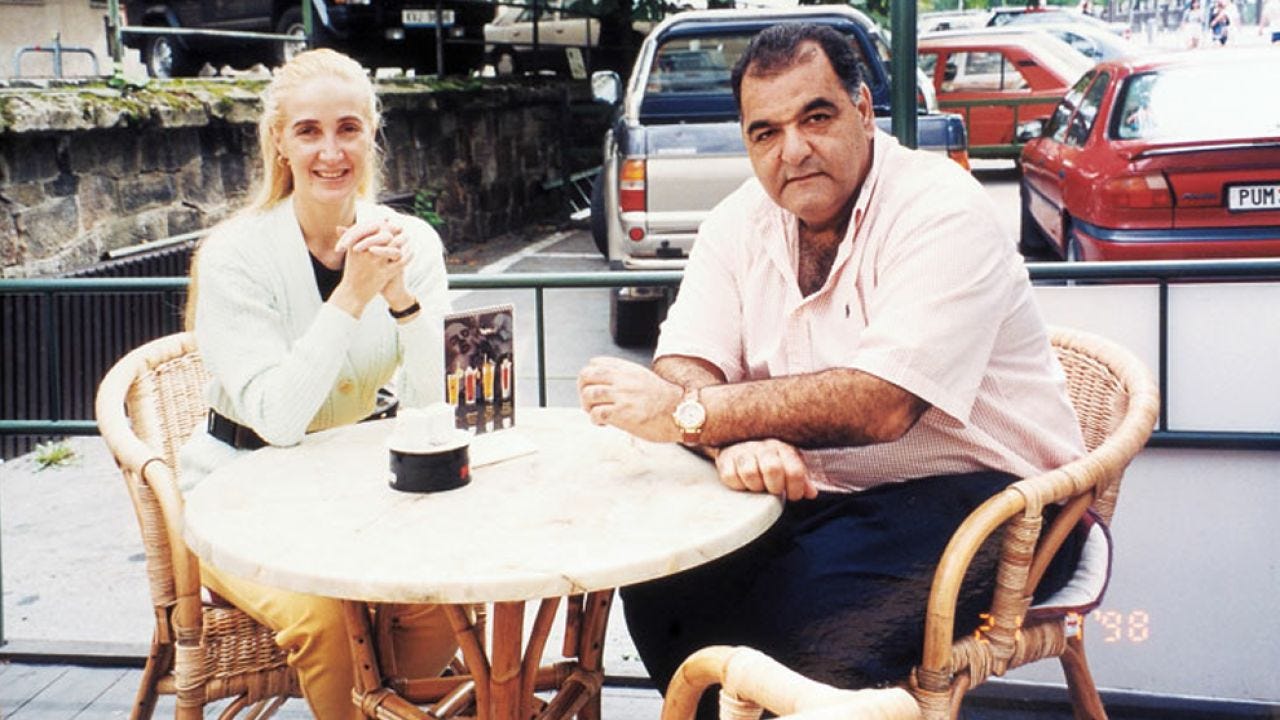

To understand this last part, Menem cannot be our protagonist of story. Instead, this narrative will follow a man who looks the part of a mafia boss — the president’s brother-in-law, Emir Yoma.

For most of the neoliberal Menem years — when the economy was growing, inflation low, and the popular classes too confused to know who their enemies were (see Adamovsky, 2012: 31-45) — Emir was single-handedly the cause of most bad press that the administration received, owing in turn to his penchant — to put it frankly — for doing crimes. It is ironic that Argentine media adopted the “-gate” suffix to refer to Menem-era scandals, since Nixon only had one Watergate to his name. By comparison, the number of such in ‘90s Argentina is beyond counting — though two are most notable prior to the Big One that will be discussed below. First, Swiftgate — in which Emir tried ham-fistedly to extort the Argentine subsidiary of meatpacking multinational Swift — resulted in his removal as a presidential advisor, without impacting in any real way the power Emir Yoma wielded over and on behalf of his brother-in-law (Santoro, 2001: 356). As will be seen, this came from more, shall we say, unofficial, sources than any title. Second, in the — rather uncreatively named — “Yomagate,” Menem’s sister-in-law, Amira Yoma, was ignominiously fired from her own position in the Casa Rosada after it emerged that she had been using it to funnel money into narco-trafficking linked bank accounts in New York. This was not just another bizarre or extraneous scandal. It had to do with Emir’s powerful — and even shadier — friends, whose vital assistance Menem forced him to keep the Yomas around. Even if they were the in-laws from hell, and even if the marriage of Menem — a notorious womanizer — to Zulema Yoma (Emir’s sister) was never exactly idyllic.

Monzer Al Kassar was born in Yabrud, Syria — sometime in the late 1940s, the exact date is unclear — to a local notable who had risen high under the Ba’ath, serving as Syrian ambassador to India among other countries. Young Monzer would seem, at first glance, to be a problem child who failed to live up to his father. Before turning thirty, he had already faced criminal proceedings in at least three European countries, for dealing in stolen cars and drugs. But Mohamed Al Kassar, in terms of raw achievement, would soon to be left in the dust by his son.

There’s that old joke about how boomers scold the young for not working hard but their own paths to a career were absurdly easy. Something similar was at play in the global arms trade during the high Cold War. Nowadays you have to be some kind of Israeli or American ex-special operator to get ahead in that business. In the early-70s, though, Monzer was able to break in with no more start-up capital that whatever he had accrued supplying hash to the Danish hippie scene. From there, he called up some contacts in Bulgaria and — to a lesser extent — Poland, and bam, an empire was born.

It was in his role as arms trader that Monzer Al Kassar first appeared in Argentina. In 1972, he traveled to La Rioja seeking to make connections among the Syrian diaspora there. Two of these would later evolve into long and fruitful partnerships. One was of course with the Yoma family, one of the wealthier and more prominent in the Syrian community. The other was with a young up-and-comer named Alfredo Yabrán (Sanz and Paolella, 2007: 59-61).

Yabrán is one of the more bizarre characters in Argentine history and (as I find myself saying so frequently during this series) could have an entire series just devoted to his own biography. In 1998, Yabrán infamously committed suicide after an arrest warrant was issued for him owing to the murder-for-hire of photojournalist José Luis Cabezas — whose sin, in turn, had been to photograph the intensely reclusive Yabrán with his wife on the beach. This was the first time his face would ever appear in the press. But before that, for around a decade and a half, Yabrán was one of the wealthiest men in Argentina, worth well over half a billion dollars, and owning an empire which spanned from media, to finance, logistics, printing, and airport services. The last one of these is of the greatest interest for our present story. One of the more controversial Yabrán-owned companies was an storage firm called EDCADASSA, which received in 1989 a contract — by executive decree, mind you — to run security at Ezeiza Airport outside Buenos Aires. EDCADASSA first came under media scrutiny over its placing in charge of customs at Ezeiza a Syrian national ,Ibrahim al-Ibrahim, who 1) was married to Amira Yoma (that is, then-president Menem’s sister-in-law) 2) did not speak Spanish well enough to communicate, requiring that all his instructions first be translated from Arabic and, 3) had illegally been given Argentine citizenship just eleven days after first arriving in the country (Sanz and Paolella, 2007: 9). Monzer himself would later be the subject of a very similar scandal (his permanent residency was awarded in three weeks, but at a time when his criminal reputation had already become well-known), although at least he spoke Spanish fluently — the result of a longtime residence in Costa del Sol which earned him the moniker “Prince of Marbella” (Sanz and Paolella, 2007: 15).

Side note: in another maddening sign of how nothing ever really ends in Argentina, the successor company to EDCADASSA is today owned by Aeropuertos Argentina 2000 S.A., in turn the flagship enterprise of Eduardo Eurnekian, aka Javier Milei’s former boss and biggest campaign donor. You can read more about Eurnekian here.

It should seem pretty clear by this point that something fishier than just run-of-the-mill corruption and nepotism was going on with EDCADASSA. Ibrahim was only one of the Al Kassar associates staffing it top-to-bottom. We know now, as a result of journalistic investigations into the events to be described below, that the company existed first and foremost to turn a blind eye as Ezeiza became the port of departure for large shipments of weapons around the globe. But explaining why Monzer needed such a setup in Argentina of all places requires that we go back, to what happened between his initial acquaintance with Yabrán (1972) and the events just described.

By the early 1980s, Reagan’s war against an increasingly assertive Third World had created exploding demand for weapons of all kinds, from all sources. Illicit arms traffic is not unlike trade in other commodities. The late Cold War-era arms boom had its own star brokerage house: the Bank of Credit & Commerce International (BCCI). In turn, BCCI had its own glamorous, world-renowned top trader; this was of course Adnan Khashoggi. But — stretching the Wall Street analogy further — it also had bright and ambitious junior apprentices, among whom was Monzer Al Kassar.

Monzer was involved in the deals for which BCCI is most notorious, those which which armed some of the most downright brutish cronies of the capitalist “Free World: the Contras, Ferdinand Marcos, the Afghan mujahideen, Mobutu, the Zia dictatorship in Pakistan, etc. This was not out of ideological loyalty to the United States and its Gulf allies, necessarily. Much like the infamous commodities trader Marc Rich, whose sanctions-busting earned him years spent as a fugitive from Uncle Sam (see Blas and Farchy, 2022: Chapter Four), Al Kassar was not some closet leftist but he was a capitalist so vicious that greater good of the U.S.-centered global system on which he depended could be immaterial if he stood to make a buck. This reasoning was what brought Monzer, in the early 1980s, into taking on a Western client that had fallen out of favor as his own. Argentina, still in the throes of the Proceso de Reorganización Nacional military dictatorship, had been embargoed by the Carter administration as part of its “human rights” image crusade. This was lifted by Reagan — for whom the whole notion of human rights was pinko nonsense — but then promptly put back in place, not just by the United States but by the entire Western bloc from which the Proceso so desperately sought acceptance. The reason for the course-reversal-within-a-course-reversal? Thirty thousand dead university students could be an acceptable cost of foreign policy realism; the right of British settlers to exploit petroleum and fishing stocks in the South Atlantic could not. I am referring, of course, to the 1982 Malvinas war.

The generals were caught flat-footed by the US-EU arms embargo which followed the initial liberation of Malvinas in April 1982; this was more political stunt than real national self-assertion and Galtieri et. al. expected the collective West (especially the United States) to understand that and play along even if the stunt in question took the form of a direct and potentially humiliating challenge to their imperial prerogative. In a flash, Argentina had gone from celebrated as a bulwark of capitalist civilization to demonized as a rogue Third World dictatorship; with a British armada bearing down, it was forced to turn to to the black market for arms supplies. Monzer was only too happy to step into the market niche vacated by Lockheed and Northrop Gruman. At exorbitant cost, he sold Argentina the Exocet anti-ship missiles later made famous by the sinking of British cruiser HMS Sheffield — alongside smaller-ticket items.

Argentina never had enough Exocets to win the war. But the battering delivered to the Royal Navy with the handful that they did have fired the imaginations of Argentine top brass, and created tremendous goodwill in Argentina the man who had supplied this Wunderwaffe. What would begin postwar as an effort to import-substitute the Exocet soon evolved into something much grander, as the horizon for indigenous weapons development in the global South suddenly began a rapid expansion in the final quarter of the twentieth century. The rapid global proliferation of missile technology, as well as its low cost relative to conventional air power, produced not just a strategic arms race between the superpowers but pitted an increasingly broad range of players against each other to see who could produce the most cutting-edge missile technology the cheapest. In the era of Third World debt crises, and rising prices caused by the intensification of the Cold War, weapons were an attractive source of foreign exchange. Having seen what missile technology could do, Argentina was determined not to be left out of this global race.

Two obstacles faced the generals trying to turn Argentina into a missile power. First, political will. This was overcome fairly easily as a result of the first carapintada — renegade military officer — uprising, in 1987, against new democratic president Raúl Alfonsín. The Argentine Air Force, previously the most aristocratic and über-reactionary branch — famously, responsible for strafing Peronist demonstrators on the Plaza de Mayo in 1947, killing hundreds — decided to become the most “democratic” and played a central role in suppressing the revolt. A gracious Alfonsín agreed to bless the new missile project — now codenamed Condor II — in order to keep them on-side. A similar dynamic of coup-proofing would play out in Menem’s interaction with the Argentine military-industrial complex, to be discussed shortly.

The second obstacle, funding, was initially more vexing. Argentina had a surfeit of Europe- and U.S.- trained aeronautic engineers, who were able to design the Condor, but manufacture would require physical plant that did not exist in the country and thus needed to be built from scratch. It was here that Monzer came in. BCCI and its Gulf financiers were then in the market for an intermediate-range ballistic missile for Iraq, whose war effort against Iran they were sponsoring in order to contain regional spread of the 1979 Islamic Revolution which had recently taken place in the latter country. Condor II fit the bill perfectly, and could replace outdated Soviet-manufactured SCUDs in the Iraqi arsenal. A deal was thus struck for BCCI to finance the project in exchange for the transfer of Condors to Iraq, via Egypt (Santoro, 2001: 133-138; 151-159).

Argentina was involved far more broadly in West Asian intrigue during the ‘80s. The Condor project interested Libya, with whom a contract for was also inked; Alfonsín had no geopolitical obligations to anyone and regarded weapons sales as purely a lifeline for his nation’s ailing economy. Having brought Argentina back into the Non-Aligned movement, objections by the United States were of secondary, if any, importance for him. Coherence was ranked even further down; in addition to agreeing to supply the Condor to Iraq, Alfonsín also kept up sales to its battlefield opponent — Iran — of massive quantities of conventional arms. These had begun as the obverse side of cooperation between the Proceso and the state of Israel in prosecuting the dirty wars in Central America as a favor to the United States; in the Iran-Iraq confrontation Israel partially broke with its superpower patron in order to supply hundreds of millions of dollars of arms to revolutionary Iran. Saddam Hussein represented the familiar threat of Arab nationalism, to which Israeli strategic calculus of the time held political Islam to be vastly preferable; furthermore, Israel presumed that its relationships with Shah-era military technocrats would in the long-run prevent Khomeinist radicalism from being reflected in actual Iranian policy. Israeli arms were transited by the Argentine pilots of a mysterious company called Rioplatense Air Transport (TAR); the 1981 crash of one such flight in Soviet Armenia would expose not only Israeli arms sales to Iran but the broader Iran-Contra scandal as well. In Argentina — unlike in the United States — covert operations in the faraway Middle East caused little controversy, except insofar as they demonstrated Israeli complicity with the Proceso even throughout its crimes against Argentine Jewry (Lutzky, 2012: Chapter Two; see also Santoro, 2001: 91-98). That would soon change.

Like the nation which he was elected to lead, Carlos Menem had been wheeling-dealing across the Middle East. Prior to launching his 1989 campaign, the future president made a pilgrimage to Yabrud — the town, lying just north of Damascus, where both his parents had been born. The trip to Syria was about more than just sentimentality. Hafez al-Assad had long looked beyond his immediate region for allies which could help to balance the forces which loomed over delicate Syrian national security — Israel (obviously), the United States, their proxies in Lebanon, and most recently Ba’athist Iraq. Assad’s savvy for friends on the global stage took some forms which are well-known — a close alliance with the Soviet Union, a slightly-less-close one with Iran in later years. But while important, these partnerships were never sufficient for the venerable Ba’ath party chief to rest easy and cease his close attention to global minutiae. It was thus that Syria began to discreetly cultivate links with politicians from the enormous Arab diaspora spread across the planet, but especially concentrated in Latin America. The fastest way to the hearts of these native (or in the case of Menem, less-than-native) sons was campaign finance. Menem almost certainly did not do the talking in his audiences with the Syrian leader. He was accompanied by his in-laws — Amira Yoma and Ibrahim al-Ibrahim, both of whom would have been much better placed to negotiate with Assad — and likely also by Monzer Al Kassar himself. Nevertheless, the youthful Argentine made a positive impression somehow. It probably was less Menem’s personal charisma — he did not speak a word of Arabic — than his strong left-nationalist, anti-imperialist campaign rhetoric, which secured for him millions of dollars in campaign donations from Syria (Sanz and Paolella, 2007: 28).

Normally, pista siria (“Syrian connection”) literature about the AMIA bombing pretty much ends there. It is speculated that Menem made all sorts of promises to Hafez al-Assad — a nuclear reactor, the Condor II, etc. — and that his later pro-US turn so incensed the latter man that the wreaked a bloody revenge against sites in Argentina (see for example Sanz and Paolella, 2007). This, to be clear, not the version being argued here, something I would like to think is about more than my admitted political biases (or principled commitments?) against the U.S./Israel. As will be seen presently, such an explanation of AMIA relies on seeing the hand of Assad behind the actions of Al Kassar, a leap in reasoning whose foundations are far from solid. It is true that Monzer functioned in certain moments as a Syrian intelligence asset, but it taking from this that he was a “virtual ambassador” (see Sanz and Paolella, 2007: 14) for Assad is a stretch when talking about a canny operator for whom self-interest came far before anything else (like loyalty to homeland) and who demonstrably also worked extensively with the United States and its Gulf allies.

All of which is to say that the point of mentioning the Assad-Menem relationship here is — rather than to impute anything solid from it — simply to illustrate the extraordinarily complex range of foreign geopolitical interests to which Menem was in some way subject upon entering office. He also allegedly received large campaign donations from Gaddafi’s Libya, the Gulf States (mainly Kuwait), and even Iraq — at that time, locked in a mortal rivalry with its fellow Ba’athists in Syria! But the exact things that endeared Menem to this set of interests were liabilities when it came to getting backing from other ones that were ultimately more important. Menem’s campaign-trail sympathy with the Palestinian cause — unprecedented, before or since in Argentine politics — angered the Jewish community; he would become the first Argentine president to visit Israel in part as an effort to dispel this tension (Lutzky, 2012: 37-39). Needless to say, the United States also had a host of reasons to be less-than-keen on the new Peronist president — which, however, largely evaporated once Menem assumed office and began to implement Washington Consensus economic orthodoxy. But only largely. A fly remained in the ointment in the form of the Condor II project. More than representing a threatening level of military strength from one of its Monroe Doctrine satraps — one which had gone to war against the Anglo powers in recent memory — the U.S. was concerned by plans to sell the Condor to Arab governments. Menem himself had been unaware of the extent of these; he became panicked upon meeting Muammar Gaddafi on the sidelines of the 1989 Non-Aligned Movement conference in Belgrade and learning apparently for the first time that Argentina had agreed to provide Condor II to Libya (see Santoro, 2001: 140-141). As regarded the original buyer, Iraq, the contract with Argentina now had the potential to create strategic nightmare for Washington, with Saddam having become its #1 bete noire in the post Cold War world (see Wallerstein, 1992; Pelletiere, 2001). Had he posessed the Condor during the 1991 Gulf War, rather than just some rusty SCUDs, the largely symbolic Iraqi missile strikes on Israel would have been anything but.

Menem wound up canceling the Condor II project entirely and ordering all components produced up to that point to be shipped to U.S. bases in Spain for verified destruction. In doing so, he ended not only Iraqi aspirations acquire modern ballistic missile capabilities, but also the Argentine bid to become a pathbreaking military power. Aside from putting a pin in any aspiration to recover Malvinas for the foreseeable future, this also stunted a nascent civilian space program, which had been invested with substantial national pride as it briefly appeared to be overtaking that of giant Brazil. No one was really sure where to go next. Al Kassar attempted to recoup his investment through a series of negotiations to provide dictatorship-era Argentine arms to increasingly improbable customers — impoverished Bolivia, the military government of Sri Lanka — but these were small change in comparison with the Condor deal (Santoro, 2001: Chapter Four). Menem continued his scattered efforts to ingratiate Argentina with Washington, such as by sending a naval contingent to the Gulf or withdrawing from the Non-Aligned movement. But ultimately, Argentina was not relevant to the geostrategic priorities of American empire, except insofar as what it could not do — sell the Condor II to Iraq, reopen the Malvinas conflict. Yet.

One sunny morning in March 1998, an old man living just outside Buenos Aires was bemused to be confronted by a TV news crew while doing the gardening. Upon hearing what they wanted to talk about, he readily confessed to being one of the most senior Holocaust perpetrators then-living.

Dinko Šakić had served as commandant of Jasenovac — “the Auschwitz of the Balkans” — where around 500,000 Jews, ethnic Serbs, Roma and communists had been murdered, largely using knives, axes and farm implements rather than the hyper-modern methods of the Germans. Like other senior officials of the Nazi-allied, clerical fascist Independent State of Croatia (NDH), Šakić escaped the victorious Partisans and emigrated to the New World through “ratline” networks operated by the Vatican. There, he languished for decades in the political wilderness, trying mainly to stay one-step-ahead of the Yugoslav intelligence agency UBDA, whose daredevil targeted assassinations of collaborationist figures living in Argentina were such that the famous Mossad operation to seize Adolf Eichmann from the country looks tame by comparison. Šakić, like other Ustasha exiles, harbored ambitions to return home and overthrow the hated communists. The international Croatian fascist underground, however, was riven by infighting, as it divided between a more conservative wing loyal to Poglavnik (Führer) Ante Pavelić (who also resided in Argentina prior to an assasination attempt in 1957) and an ideologically flexible, more ruthless one led by Vjekoslav “Maks” Luburić, who had occupied a bureaucratic position roughly equivalent to that of Eichmann in the Nazi hierarchy, organizing and overseeing the Ustasha network of extermination camps. Luburić, who during the later war years had urged that the Ustasha switch sides from the doomed Axis and sell itself to the Western Allies as an anticommunist bulwark (see Tomasevich, 2002: Chapter Eighteen), now — so Miroslav tells me — was interested in a potential alliance with the Soviets following the Tito-Stalin split, something that was even more anathema to the orthodox Pavelić faction. The Luburić group (Croatian National Resistance, or Otpor) was, however, by far the more the more active one in the postwar decades, committing spectacular if totally ineffectual acts of terrorism against Yugoslav targets, mainly in the form of airplane hijackings. They also lashed out against a West judged insufficiently committed to the holy war against communism, famously by bombing a baggage claim at New York’s LaGuardia Airport in 1975.

By the 1990s, that had changed. The disintegration of Yugoslavia had brought Franjo Tudjman — a Partisan veteran who had undergone a born-again conversion to right-wing Croatian nationalism, Ustasha apology, and Holocaust denial — to power in a now-secessionist Croatia (Hayden, 2007: 37-40; 149-151; 158-160. Tudjman strongly courted the Croatian diaspora, especially its Ustasha veteran subcommunity, whose financial support he desperately needed to equip the paramilitaries facing off against far better-armed and more professional Yugoslav federal forces. While donations mostly came from the larger and wealthiest diaspora communities — Toronto, Chicago, New York and Sydney (see Hockenos, 2019) — Tudjman and his defense minister, Gojko Šušak, also made a stop in Buenos Aires on their world fundraising tour. In 1992, he pleaded for Argentine support in a ceremony at the private Croatian school in Hurlingham, Buenos Aires (itself named for the Nazi collaborator Cardinal Alyosius Stepinac) that was attended by Carlos Menem. Though Menem later feigned shock when the residence of Dinko Šakić was reported in the media, he had in fact already met and shook hands with the ex-commandant during the Stepinac event years earlier (Lutzky, 2017: 23-24).

To be sure, Menem’s decision to sign two secret, highly illegal orders authorizing the transfer of weapons and ammunition to Croatia was not primarily a result of the lobbying of decrepit war criminals and a tinpot Balkan dictator. It seemed to offer an incredibly elegant solution to a number of problems. First, what would end up being 6500 tons of arms supplied — mostly basic conventional items, like 155mm artillery shells — came largely out of existing stocks and were not replaced, part of a broader debilitation of the Argentine military under Menem. Having himself faced a carapintada uprising, in 1990, Menem sought coup-proofing measures as had Alfonsín. The difference was that the neoliberal Menem, rather than trying to positively harness the energies of the military brass away from political interventions and towards national development projects (like the Condor II), simply saw another part of the Argentine state that he wished to trash. Second, the Yugoslav wars were Menem’s long-desired “big break” with Washington. Ensuring the disintegration of Yugoslavia was vital to the post-Cold War neoconservative plan to assert more-or-less direct control over Eurasian energy resources, and in so doing arrest the decline of American hegemony (Achcar, 2023; see also Harvey, 2003: Chapter Two). Given its control of naval access to the western Balkans, arming Croatia was a necessary first step before weapons could be transited to the US-favored Bosnian Muslims. Iran was then providing extensive material support to Bosnia — having judged pan-Islamic causes to be a higher priority than anti-imperial ones — but, mindful of Iran-Contra and its fallout, the Clinton administration was too cautious to openly embrace this strange confluence of interests. Argentina, given its Proceso-era links with Iran, was thus an ideal intermediary between this country and the West in a conflict where both were effectively on the same side but unable/unwilling to cooperate directly (Santoro, 2001: 218-224). But most important, and simplest, of all was the existence of a UN arms embargo on the Balkan conflict zone. The United States, unwilling to risk the embarrassment of violating this directly, once again outsourced its dirty work to a servile Argentine government. Menem was only too happy to oblige, which brings us to the third reason. The Croatian traffic made money for the Yomas and Al Kassar, but in a way that unlike the prospective Condor II deal caused no problems with Washington. It seemed possible for Menem to make everyone happy after all.

What happened next is probably familiar to most people reading this. Croatia turned the tide of the war, enabling it to carry out the single largest ethnic cleansing to have taken place in post-1945 Europe — the forced expulsion of around a quarter of a million ethnic Serbs from its own rebel Krajina region (Hayden, 2007: 104-106). Yugoslavia was roundly fragmented, though securing this outcome would ultimately require direct NATO bombing. Most of the western Balkan countries are now safely ensconced within NATO, a few are even (relatively) prosperous members of the EU, and the rest are safely kept in line from the heavily militarized protectorate of Kosovo. Arguably, this is the only part of Eurasia where the strategy for imperium actually had success — at least, it worked compared to in the Middle East or former USSR.

For the Argentine participants, things worked out less idyllically. Menem and Emir extended their gun-running activities into a harebrained scheme to arm Ecuador in its brief 1995 border conflict with Peru. When the arms-trafficking finally became a scandal, it was largely because of this; Menem had betrayed a traditional Argentine ally and taken a side that was overwhelmingly unpopular in the broader region (see Santoro, 2001: Chapter Seven). He, Emir Yoma, and various other participants working at the state-owned Fabricaciones Militares faced extensive criminal proceedings and even jail time. Monzer Al Kassar was forced out of the shadows, he briefly became a household name in Argentina and his relationship to Emir was mocked by sketch comedy programs. But then Menem’s neoliberal finally lunacy destroyed the Argentine economy, and people had bigger things to worry about.

Why tell this story as the conclusion to a series about the AMIA bombing?

This series has sought to critique the official line that Iran and/or Hezbollah were responsible for AMIA and the 1992 Israeli embassy bombing; it contends that this story exculpates participants within the Argentine state while being politically convenient for American empire. But there was a third bombing that happened in 1990s Argentina, for which Iran was never blamed — for which we know Argentine state actors were responsible — which might shed light on the other two. On 3 November 1995, the explosion of an arms factory in Río Tercero, Córdoba produced a mushroom cloud over that small city, killing seven bystanders and injuring hundreds more. In spite of implausible claims that the blast had been accidentally triggered by a stray cigarette butt, we know now beyond the shadow of a doubt that the factory was deliberately dynamited by Fabricaciones Militares bureaucrats in an inept effort to cover the dispatch of illegal arms shipments to Croatia and Ecuador from it (see Santoro, 2020). Is such sloppiness a contrast with whoever was responsible for the AMIA bombing, since that party has never been caught? Or was the truth about Río Tercero simply less unspeakable, given the lower international relevance?

We have discussed the lack of evidence that the AMIA attack was carried out via suicide car bomb.

Minutes prior to that explosion, a dump truck deposited “construction materials” in front of the AMIA building, which had never actually been ordered. A form allegedly signed by the architect contracted to oversee then-ongoing renovations of AMIA was later conclusively proven to be a forgery. The mysterious dump truck and its the uniform worn by its driver both clearly marked him as employed by a construction company whose owner was the Syrian-Lebanese dual national Nassim Haddad, in turn a close associate of Monzer Al Kassar. Haddad was further unable to explain his purchases of huge quantities of ammonium nitrate — the explosive used in the AMIA bombing — in the prior months. He was arrested, but released mere hours later at the personal request of Col. Carlos Franke — head of Fabricaciones Militares, and a key player in organizing the arms shipments to Croatia (Lutzky, 2012: 22). Mind-bogglingly, Haddad’s company was then contracted to clear rubble from the AMIA blast site, rubble which was of no forensic interest to Federal Police investigators who had begun insisting on the existence of a phantom Renault Traffic suicide van even before rescue efforts had started (Lutzky, 2012: 38; Levinas, 2014: 49-50).

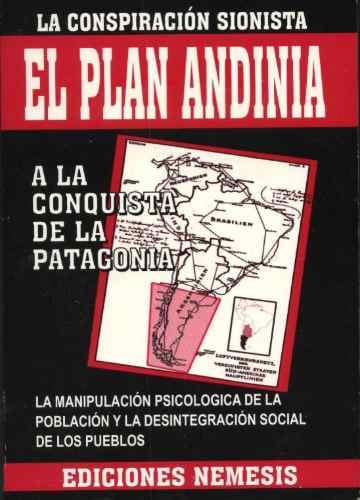

Speaking of the Federal Police, in 2000 a man claiming inside knowledge of the AMIA attack approached Horacio Lutzky, editor-in-chief of the small Labor-Zionist (I know, but bear with me for a second) newspaper Nueva Sion and one of the most outspoken skeptics of the official story. Lutzky, who had dealt with similar cranks before, was initially dismissive — until he heard the man’s extraordinary tale, one which turned out to be one hundred percent factual. José “Iosi” Pérez had spent over fourteen years impersonating a Jew in his role as an undercover Federal Police agent looking for evidence of something called the Andinia Plan. This is a venerable antisemitic conspiracy theory on the neo-Nazi Right in the Southern Cone, which holds in its broad outlines that some type of Judeo-Bolshevik plot exists to seize Patagonia and transform it into a second Jewish state. It found true believers at the highest levels of the Proceso security apparatus, whose — counterrevolutionary, first and foremost — violence also had a strong antisemitic tinge, with Argentine Jews being targeted at vastly disproportionate rates and Jewish detainees tortured specifically for information about the Andinia plot (see Porter, 2020). Note that “Iosi” was sent undercover years after the return of democracy of 1983. The Federal Police, as his account makes clear, remained dominated by avowed neo-fascists and procesistas.

Pérez sheds light on one of the strongest indications of Argentine state complicity in the AMIA (and 1992 Israeli embassy) attacks: the inexplicable disappearance of Federal Police security details during the hours in which they were bombed (Lewin and Lutzky, 2015: 15-17; 78-79; 103-104). He further has evinced certainty that the intelligence he gathered — which included building plans for the AMIA — was used to carry out the bombing and/or cover it up, a claim which seems corroborated by witness testimonies to the effect of there being multiple explosions and/or an explosion from within the building (Levinas, 2014: 35-36). Cover up for who? No doubt, the far-right dinosaurs in the Federal Police had the ideological motivation to massacre Argentine Jews. But let us try to complete a circle between them and the murky interests described above.

We have discussed Carlos Saul Menem.

I mentioned before how “La Pista Siria” is typically invoked to explain the embassy/AMIA bombings as a mafia-style vengeance against Menem for his broken promises to the Syrian state. This narrative is strengthened if you believe that the death of “Carlitos” Menem Jr. in a 15 March 1995 helicopter crash was in fact the result of foul play, a proposition for which there however is no direct evidence. Zulema Yoma certainly believed that her ex-husband and brother-in-law bore responsibility, but whether she had any reason to or was simply driven mad with grief is less clear. Occam’s razor points to Menem Jr. having died in an accident, albeit one which his father cynically trotted back out years later during the Nisman furor by claiming that Hezbollah had actually murdered Carlitos. Menem Jr. aside, if someone did want to revenge themselves on Menem by wreaking carnage in the nation which he led, it does not seem clear why that party would be Assad acting via Al Kassar as opposed to just Monzer himself, who had lost millions at a stroke of Menem’s pen when Condor II was canceled. Even this seems slightly contrived. What I really wish to suggest here is not that AMIA happened as a result of some type of personalized Bond-villain revenge plot, but instead represented blowback as a structural feature of Menem’s Argentina. In which case, given the nationality of so many key players, “La Pista Siria” would still seem to be a convenient shorthand. The comically long rap sheet of Emir Yoma shows how, to riff on Charles Tilly (2017) for a moment, the making of a neoliberal Argentine state under Menem took place as a process of organized crime. Specifically, in trafficking arms to Croatia on behalf of the United States, Menem had set in motion a dangerous situation in which Buenos Aires was flooded with untraceable guns and explosives. Furthermore, these were put in the hands of volatile actors, from Levantine mafiosi to Proceso-era military officers and spooks, to whom political violence came naturally. Links between AMIA and right-wing Croatian groups also would seem to deserve further research given the long, transatlantic career of Ustasha exile terrorism.

We have talked about Jaime Stiuso, and his creation — Alberto Nisman.

Besides providing Nisman with the material to make various frivolous cases against Iran, Jaime also steered him away from investigating anything related to “La Pista Siria.” The U.S. embassy in Buenos Aires also requested Nisman abstain from doing so, as revealed by Wikileaks (Young, 2015: 184-185; Duggan, 2019: 66-72).

Finally, we have talked about Israel and the Jews of Argentina.

Yet another Syrian-Argentine who was a Menem intimate is Ruben Beraja, whose tenure as DAIA chief coincided with the latter’s presidential mandate. Beraja was a participant in the notorious US $400,000 payoff to witness Carlos Telleldín — about which, more here — and by the late ‘90s had become a fairly controversial figure, in spite of his repeated protests about supposed “victim-blaming.” Memorial groups and what of the Jewish left which had survived the Proceso increasingly began to harass him wherever he went, demanding that justice extend past phantom Iranians to the various Menem associates implicated in AMIA. Ruben Beraja got the last laugh, though. The failure of his own Banco Mayo, in which almost all Jewish institutions kept their funds, enabled a restructuring of Argentine Jewish life which substantially marginalized left-wing factions from the governance of DAIA and other national umbrella organizations. In their place came religious and Zionist hardliners, awash in foreign donations, who remade the public face of Argentine Judaism in their image and swept any inconvenient questions about AMIA under the rug. Chief among these was the missionary cult Chabad-Lubavitch, whose relief efforts for Jewish families left destitute by the 2001 crisis pulled them from standing at the barricades with gentile peers (Lutzky, 2012: Chapter Seven). The first major revolt against neoliberalism in the twenty-first century was also the first in Argentine history where Jews hewed in large numbers to the side of reaction — a trend which has continued to deepen ever since.

In 2023, Argentina elected a president who was exactly what he seemed.

First, no one ever thought of Javier Milei as a conventional macho. The president is unfailingly obedient to his domineering sister, Karina Milei, his rather Oedipal bond with whom from a childhood that was traumatic in some unexplained way. Milei croons classic rock from the balcony of the Casa Rosada, he communes magically with a long-dead pet, cosplays as “Captain AnCap” and melodramatically threatens suicide via Twitter. The repressive “strongmen” in his administration are all women — Patricia Bullrich, Victoria Villaruel. Unlike Menem, who became a Catholic to fit in, Milei has fled in the opposite direction — flirting erratically with Judaism, even to the point of making a pilgrimage to the Hasidic shrine at 770 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn.

Second, no one ever thought Milei was anything but the most right-wing mainstream politician in recent Argentine history. He is the first since the return of democracy to openly downplay atrocities committed under the Proceso, he has invited American troops onto Argentine soil while eschewing civilized diplomacy with any left-of-center or non-Western government. His “omnibus” privatization of, well, everything has largely failed to become reality due to being patently unworkable. Milei’s main achievement has been to give the IMF its pound of flesh — devaluing further in order to service the massive, shady loan taken out under Mauricio Macri — in the process, bringing the inflation and cost-of-living crisis he was elected to solve to new heights.

Milei’s antics mean that unless you squint, one of the most revealing things of all about his “new” administration might be easily missed. His pick for Minister of Justice — Mariano Cuneo Libarona. Cuneo Libarona, aside from being arrested himself at one point over the AMIA cover-up, was longtime attorney to Emir Yoma and later defended his presidential brother-in-law in the various arms-trafficking cases. Cuneo is one of only many, many Menem-era ghouls who returned to staff the Milei administration and before it that of Mauricio Macri. And so, even if Milei seems more weirdo true believer that corrupt wannabe despot — in contrast to say, Jair Bolsonaro — the incestuous circles of Argentine elite malfeasance remain present in his neoliberalization project, as in all the prior ones. Hopefully, AMIA has served as a helpful entry point for starting to understand these.

References:

Achcar, Gilbert. The New Cold War: The United States, Russia, and China from Kosovo to Ukraine. Haymarket Books, 2023.

Adamovsky, Ezequiel. Historia de las clases populares en la Argentina: desde 1880 hasta 2003. Sudamericana, 2012.

Aguiló, Ignacio. The darkening nation: Race, neoliberalism and crisis in Argentina. University of Wales Press, 2018.

Blas, Javier, and Jack Farchy. El mundo está en venta: la cara oculta del negocio de las materias primas. PENINSULA, 2022.

Duggan, Pablo. ¿Quién Mató a Nisman? C.A.B.A.: Planeta, 2019.

Hayden, Robert M. From Yugoslavia to the Western Balkans Studies of a European Disunion, 1991-2011. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

Hockenos, Paul. Homeland calling: Exile patriotism and the Balkan wars. Cornell University Press, 2019.

Levinas, Gabriel. La Ley Bajo Los Escombros: AMIA, 20 Años de Encubrimiento Estatal. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 2014.

Lewin, Miriam, and Horacio Lutzky. Iosi, El Espía Arrepentido: La Confesión Del Policía Federal Infiltrado En La Comunidad Judía. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 2015.

Lutzky, Horacio. Brindando Sobre Los Escombros: La Dirigencia Judía y Los Atentados: Entre La Denuncia y El Encubrimiento. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 2012.

Lutzky, Horacio. La Explosión. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 2017.

Pelletiere, Stephen C. Iraq and the International Oil System: Why America Went to War in the Gulf. Westport, Conn: Praeger, 2001.

Porter, Gareth. “How a Police Spy’s Stunning Testimony Threatens the Official US-Israeli AMIA Bombing Narrative.” The Grayzone, July 27, 2020. http://thegrayzone.com/2020/07/26/police-spys-testimony-official-us-israeli-amia-bombing/.

Santoro, Daniel. “Hoy se cumplen 25 años de la voladura de la fábrica de Río Tercero, tras el contrabando de 6.500 toneladas de armas a Ecuador y Croacia.” Clarín, November 3, 2020. https://www.clarin.com/politica/hoy-cumplen-25-anos-voladura-fabrica-rio-tercero-contrabando-6-500-toneladas-armas-ecuador-croacia_0_p0eVlD90T.html.

Santoro, Daniel. Venta de armas: hombres de Menem: la investigación periodística que reveló el escándalo del tráfico a Ecuador y Croacia. Planeta, 2001.

Sanz, Christian, and Fernando Paolella. AMIA: La Gran Mentira Oficial. Santa Fe: El Cid, 2007.

Tilly, Charles. "War making and state making as organized crime." In Collective violence, contentious politics, and social change, pp. 121-139. Routledge, 2017.

Tomasevich, Jozo. War and revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945: Occupation and collaboration. Vol. 2. Stanford University Press, 2002.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. "The collapse of liberalism." Socialist Register 28 (1992).

Young, Gerardo “Tato.” Código Stiuso. Grupo Planeta Spain, 2015.

Hi do you have a link to somewhere that says that the court didnt “rule” the bombing was iran