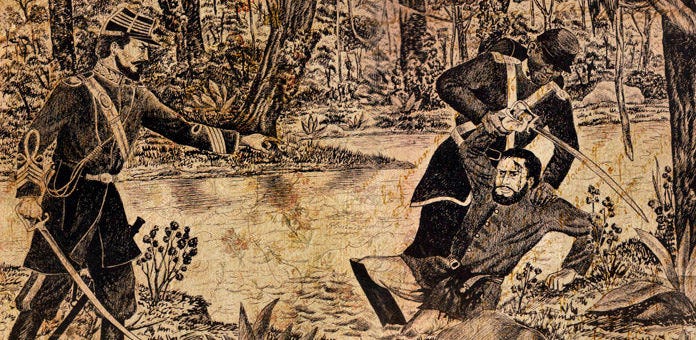

The year is 1870. Francisco Solano López, the legendary if enigmatic Paraguayan nationalist, stands wounded and alone. What remains of his army has just been crushed in a doomed last stand on a remote hill in northern Paraguay. López is by this time a president without country or a capital — the latter having been captured by Argentine and Brazilian troops the previous year. An officer of the Imperial Brazilian Army approaches López and bids the president to save himself and surrender. But Francisco Solano López is not a man who surrenders. He charges the Brazilian with his sword, screaming either “¡muero por mi patria!” or “¡muero con mi patria!” and is struck from this mortal plane. If López said the latter, he was not far off. A majority of the Paraguayan population has died over the past five years of fighting, among whom are up to 90% of nation’s men and boys. It is proportionally the deadliest conflict in human history, and the true victor is neither Brazil nor Argentina but a far greater power across the Atlantic.

The year is 2015. In an admittedly less heroic suicide, the prosecutor Alberto Nisman enters the bathroom of his apartment in the ultra-upscale Le Parc building in northern Buenos Aires. Nisman places a borrowed .22 Bersa Thunder handgun to his temple, and pulls the trigger. His body will not be discovered for some time — but when it is, Argentine politics will be set alight like rarely before.

López and Nisman. You could hardly think of two more different men, or more different deaths. But Nisman has spent his career fighting battles of a different but equally dramatic sort in the dark spaces that lie under the façade of Argentine democracy. And like López, Nisman is merely a cog in the machinations of far greater powers. One to the north, one to the east, and one in Buenos Aires itself. But we are getting far ahead of ourselves.

What these two suicides have in common is that both are ultimately the result of imperial contestation over an area that is today aptly called the Tri-Border region. The borders of Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil meet at the geographic point where two mighty rivers, the Iguazú and the Paraná, flow into each other. Before that happens, though, the Paraná is dammed twice, once at the Argentina-Paraguay border and once at the Brazil-Paraguay one. The Yacyretá and Itaipú, respectively, produce huge amounts of electricity for Paraguay from which it earns foreign exchange by re-exporting to Brazil and Argentina. La Triple Frontera also boasts some neat features of natural hydrology, most prominently Iguazú Falls, the largest waterfall system in the world — which like the lesser Niagara, are split by a national border. I myself have not yet managed to visit the falls. But I have seen from further downstream the genuinely awe-inspiring result of the rivers meeting — the Rio de la Plata, by far the widest river on Earth. Where does all this water come from? The Tri-Border Area sits atop the Guaraní Aquifer, the world’s second-largest source of fresh water — the largest being the Siberian Aquifer (Borón, 2013: 71). Which is rather inconveniently located, in more ways than one.

The Tri-Border Area is also the place from which the AMIA bombing, in the most common telling, is supposed to have been planned and carried out. I should at this point clarify that the Triple Frontera is home to a large Middle Eastern diaspora community, made up mainly of Lebanese and Syrians. However Islamophobic, the notion that there are terrorists among their ranks is a key feature of the narrative that we are examining today. SIDE, the former Argentine intelligence agency, based their original fingering of Hezbollah on phone record data from the Tri-Border Area. What this basically means is that SIDE analysts uncovered calls made from Buenos Aires to phones located in the Triple Frontera that had also been used to call allegedly Hezbollah-linked numbers in Lebanon (Blinder, 2011: 11). It’s all very vague, and the fact that the names of the suspected Hezbollah operatives making the calls have remained mostly withheld doesn’t help. One of the individuals allegedly involved in this suspicious game of Telephone is Mohsen Rabbani, the former cultural attaché to the Iranian embassy in Buenos Aires. Rabbani is one of the central figures of the official case, since he is alleged to have purchased the van used to carry the bomb. But the argument made by SIDE is based on a call made to the Triple Frontera from an area of Buenos Aires where Rabbani rented property — which falls rather short of smoking-gun proof (Porter, 2008). Even if there was conclusive evidence that Rabbani himself called a certain region, it’s not clear what this would prove. Phone analysis is not a refined tool, it can connect geographical locations where suspects could have been but rarely the suspects themselves.

Indeed, phone “link analysis” has long-ago been abandoned by intelligence agencies in Europe and the United States on the basis that it more often than not produces unprovable and/or completely false leads. Even James Bernazzanni, sent to Argentina by the FBI’s Hezbollah desk with the express purpose of helping prove Iranian guilt in the AMIA bombing, was horrified:

"It [link analysis] can be very dangerous. Using that analysis, you could link my telephone to bin Laden’s” (quoted in Porter, 2008).

The reason for SIDE being so stubborn on the issue of using was not some stereotypical Latin American incompetence. Phone surveillance was a long-running passion of agency top bosses, who throughout its existence obsessively sought a unique level of access to the phone records of Argentine citizens (Young, 2015: 69-70). By 2001, agency godfather Jaime Stiuso had secured for SIDE a total monopoly on phone surveillance in Argentina, which it could conduct without permission of judicial authorities or indeed of anyone. Not only was SIDE not subjected to oversight, courts and other police agencies could not access phone recordings without SIDE consenting (Young, 2015: 151) — a reversal of how surveillance legally works in literally any other country. All of this is to say that phone surveillance was an essential part of the mystique SIDE sold to democratically elected Argentina politicians. Stiuso’s power depended on selling himself as a loyal servant of the public state, but one with such vast powers that he was indispensable to have on your side. Because phone surveillance was an asset which only SIDE possessed, encouraging and promoting its being used as extensively as possible served to give the agency more sway over investigations.

As a result of the AMIA attack, the electronic surveillance whiz kids were far from the only SIDE employees with more on their plates. The agency also enormously expanded its boots-on-the-ground activities in the Tri-Border Area, as Tato Young summarizes in his outstanding book, Código Stiuso:

“The blast, which had been felt in much of Buenos Aires, also impacted SIDE. The relationship that it maintained with the secret services of other countries was up until that point had been well-mannered, some favors and nothing more. The explosion at the embassy was going to change all that. In the months following the attack secret cables began to be sent all over the world, the majority of the people delegated had to be switched out for those that better understood how the world functioned, headquarters and the secret bases began to receive routine visits from emissaries of the CIA, from Mossad, and from those representing the intelligence services of major European countries. Some areas of headquarters were more affected than others. The Directorate of External Intelligence had to open, at the request of the CIA, a secret base in Foz de Iguazú, in the Tri-Border Area between Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina, in order to have some control over the thousands of Brazilians of Arab extraction that had been living there for decades. The Directorate of Counterintelligence, in its base at United States Street, received from the Foreign Ministry control over the entry into Argentina of all citizens of Arab countries. Whenever an Arab wanted to enter Argentina, the base sent his/her name to the delegates from the CIA and Mossad in Buenos Aires. Within twenty-four hours those agencies would inform SIDE if that person was or was not on their list of terrorism suspects. Only then did SIDE approve and certify the good faith of the visitor, just like how in earlier times it had certified if one was or was not a communist, if one was or was not a guerilla” (Young, 2015: 80-81).

Note: in Young’s narrative this passage actually appears in relation to the 1992 bombing of the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires, rather than the AMIA bombing two years later. I have nevertheless chosen to translate it here because it provides a good overview of SIDE activities relating the Tri-Border Area as well as the interest of intelligence services in the imperialist countries in this region. The base in Foz de Iguazú, for instance, significantly increased in importance following the AMIA bombing (Young, 2015: 122-123). Both bombings are typically regarded as connected events, a view with which I happen to agree. Where that narrative and I diverge is on the ascription of blame to Hezbollah, which I do not think was responsible for either. For reasons of narrative coherence and space the Israeli embassy bombing will not be discussed in this series even though it is itself a deeply fascinating event. The choice to focus on the AMIA is due to its far greater prominence in Argentine national memory and much more significant ongoing political effects. No doubt, both are due to the more horrific nature of the AMIA attack given both its vastly higher death toll and totally civilian, totally non-political target.

The twin terrorist attacks in Argentina served to inaugurate a new era of Washington-backed securitization and militarization of the Triple Frontera. Indeed, it would not be exaggerating to say that this region, so absent from popular leftist histories of American imperialism in Latin America is viewed by the United States as its foremost concern in the entire Western Hemisphere. From the 1990s onward, American security officials and think-tankers have fervently argued that the Tri-Border region is a hub of terrorism, typically of Islamist inflection. At the height of post-9/11 hysteria American officialdom even fretted that even Osama Bin Laden himself could be hiding in this corner of South America, plotting a second attack (Young, 2015: 150). But Al Qaeda has ultimately only been spoken of in relation to La Triple Frontera in the same breath as Shia militant groups like Hezbollah. As I observed in the last installment of this series, the Iran “frame-up” (Porter, 2008) seems unlikely to actually be primarily about Iran. American and Israeli attempts to paint the Islamic Republic as a state sponsor of terrorism have not primarily revolved around the AMIA case or even always referred to it. Again, to brutally simplify — if AMIA were a “false flag” done to justify aggression against Iran, wouldn’t it have happened in the United States? The majority of Americans (Jewish or gentile) never heard of the terrorist attack in Argentina, nor could they get that worked-up over something that happened in a country so remote to their imagination. Demonization of Iran as a threat to Middle East security mainly makes reference to its sponsorship of attacks on Israeli civilians or on its nuclear program far more than to AMIA. Because the AMIA has had such little impact outside of Latin America, we must conclude that its political utility to imperialism has to do primarily with Latin America.

Now, some Arab friends with whom I have discussed the AMIA case extensively (shoutout @kousbaite on Twitter) might see my dismissal of the frame-up as awfully flippant. They would have a point, given the prominent Israeli involvement that runs throughout the history of the AMIA investigation(s) pointing to Iran. Wouldn’t Israel be primarily interested in smearing Hezbollah, which thwarted Zionist designs on Lebanon and which is a vital ally of the Palestinian resistance? What does Israel care about Latin America in itself? The Middle East frame-up versus American interests in Latin America scenarios do not need to be opposed in this way, however. Remember that AMIA is not just an attack of which Hezbollah has been accused but one targeting a specifically Jewish community institution. Argentina has one of the largest Jewish diasporas in the world, a fact of obvious political relevance for Israel. Fighting to uncover the truth of the AMIA bombing helps bolster the image Israel seeks to project as guardian of the Jewish people anywhere in the world. More specifically, the bombing inevitable caused among Argentine Jews some feeling of our endangerment in Argentina as Jews. This I can personally attest to from how my own family, as well as representatives of the Chabad movement to which we have an on-again off-again affiliation, reacted to the death of Alberto Nisman. Israel never lets a traumatic event for the diaspora go to waste. Most obviously, of course, is how the previously marginal Zionism was only able to gain widespread political support from world Jewry in the reactive, fear-filled climate that followed the Nazi Holocaust. But there is also a fascinating, if fragmented history of Israel taking political advantage specifically of terrorist attacks on the institutions of diaspora communities. The mass migration of Arab Jews to Israel was spurred in large part by panic resulting from bombings targeting them, most prominently in Iraq. Some if not all of the bombings of Iraqi Jewish targets were false-flag operations carried out by Israeli intelligence itself, assisted by local Zionist allies (Uddin, 2023). I do not believe that the AMIA bombing was committed by Israel — but nevertheless, history is illustrative of the political salience of events like it to Israeli interests. Argentine Jews, although geographically located in the periphery, are far more economically comfortable than Middle Eastern or post-Soviet communities that immigrated to Israel en masse. But success and lack of marginalization doesn’t stop the Israeli government from trying to use spectacular incidents of antisemitic public violence to encourage emigration. One only need remember Benjamin Netanyahu’s message to French Jewry following the 2015 mass shooting at a Paris kosher supermarket: France, and Europe in general, are not safe for you. Come to Israel (Lazaroff, 2015).

More speculatively, although Israel itself may not be interested in Latin American geopolitics, it does have a long history of acting on behalf of American interests in this region. The Carter Administration, when trying to rebrand American power as concerned with human rights, outsourced to Israel the task of arming its most unsavory clients in Latin America: Videla, Pinochet, the Contras, etc.. In early 2001 the Argentine newspaper Pagina12 published the name and face of Ross Newland, long-standing CIA liaison to SIDE. Newland, his cover forever blown, had to leave Argentina immediately to be reassigned a desk job at Langley (Young, 2015: 147-150). Did Mossad step in to coordinate things when its American counterpart ran into such difficulties? We probably can never know this, so let’s at least examine the details and purpose of CIA-SIDE cooperation when things were running smoothly.

Militarization of the Tri-Border Area has been far more than simply discursive. As alluded to above, a chief result of the AMIA bombing was the relationship between SIDE, the CIA, and Mossad becoming far more intimate. It would be very wrong to depict SIDE as hapless Latin American pawns, however. Agency officials did not passively take orders from Washington but actively sold the Tri-Border Area terrorist threat narrative hard to their American counterpart. American funding to the tune of millions provided for a highly sophisticated SIDE operational infrastructure in the Triple Frontera (Young, 2015: 164-165), from which both sides benefitted. The United States was able to project power into and to monitor the region, while SIDE made itself increasingly indispensable to them. Privileged links with foreign intelligence services secured SIDE in its position as top dog of the Argentine security state, while also increasing its influence over the president and other elected officials. We will have to cut discussion of SIDE short here, but we will return to its role in this story in a planned later entry about Jaime Stiuso. The man who gave the United States and Israel the AMIA, and in the process gained his wildest dreams and then some.

There is a Latin American, left-wing, anti-imperialist counterpart to American paranoia over the Tri-Border Area. Intense interest in it from the imperialist countries has, unsurprisingly, given rise to fears of their direct military intervention in this part of South America. Rumors of covert American bases in the Triple Frontera have gone around for years in spite of official denials. For example, a U.S. Embassy-sponsored “Disaster Preparedness Center” in the Argentine northern province of Chaco spawned controversy due to having an attached airstrip which was thought to make possible the local deployment of American troops (Borón, 2012). The denial that such installations exist by Triple Frontera governments, coupled with the remoteness of the region, make it hard to tell reality from anxious speculation. I think it is highly unlikely that any democratic Argentine government has permitted an American military presence to be established in Argentina, since it would require overwhelmingly unpopular legal changes such as providing extraterritorial immunity.

Speaking of extraterritorial immunity, though, one of Argentina’s Tri-Border neighbors does have laws on the books providing such for American soldiers: Paraguay. Here we are on fairly solid ground when talking about United States military presence in the Triple Frontera. Following the passage of Paraguayan immunity legislation in 2005, hundreds of U.S. Marines arrived in the country, mainly at a remote airport near the city of Mariscal Estigarribia. The Mariscal Estigarribia airport, built in the late 1980s, is larger than that of the Paraguayan capital Asunción. Left-wing, anti-imperialist writers widely state that the United States funded its construction, although I could find no solid sources on this. What is true is that the airport infrastructure can accommodate landings by exceptionally oversized aircraft, odd in a remote region that does not lie on any major cargo routes. Does this mean it is built with, for instance, the U.S. military’s C-17 Globemaster troop transports in mind? Both the Paraguayan and American governments strenuously deny that there is any permanent military presence at Mariscal Estigarribia, and English-language writing about it is exclusively in the context of dismissing the notion of a military base as “conspiracy theory.” Local reports of American special operators at Mariscal Estigarribia have ebbed and flowed over the years. But the Paraguayan laws provide immunity for up to 16,000 American soldiers, indicating that even to the extent Mariscal Estigarribia is not fully used as a military base, it is intended to at least provide the option of having one in the Triple Frontera. In 2006, the umbrella movement of Paraguayan peasants stated that U.S. Marines had been responsible for the murder and disappearances of up to thirty rural workers in the Paraguayan Chaco who had been outspoken critics of multinational extractive enterprises. Of course, there was a blanket official denial in the form of a restatement that American troops were only at Mariscal Estigarribia for training and humanitarian purposes. But this seems less-than-persuasive given the specificity of the accusations made. In 2019, the Paraguayan government once again approved a deployment of U.S. soldiers —including Navy SEALs — to the country. Even of the nature of these deployments is officially disputed, their purpose is freely acknowledged as being to combat supposed threats emanating from La Triple Frontera. Whether those are terrorists, gun-runners, narcotraffickers, or all of the above — the United States has a clear interest in hyping up the idea of the Tri-Border Area as an anarchic, dangerous place that justifies American or allied military-intelligence activities there. The question is why.

One thing which frustrated me when doing research for this article was the seemingly resource-determinist nature of many Latin American analyses of imperialism’s interest in the Triple Frontera. This region has huge amounts of fresh water, of gas, of metals, of biodiversity, etc., and is in the Western Hemisphere, ergo the United States lusts after it as a kind of natural-resource piggy bank. It does make sense from the perspective of a Latin America incorporated into world capitalism as an exporter of natural wealth — as captured so eloquently by Galeano. And it is also true that climate change is increasingly leading imperialist countries to covet resources in their own right. Remember how the Tri-Border Area holds the largest reserve of fresh water on earth after Russia’s Siberian Aquifer — which, for political reasons, is obviously off-limits to the United States. The extreme material intensity of the American consumer economy makes any kind of resource crunch acutely threatening, and causes a search for fixes conveniently located in its Monroe Doctrine backyard (Borón, 2013: 64-76). Returning to the Guaraní Aquifer, for instance, one can see how access to such a bounty would be very helpful for a United States that has a growing proportion of its population living in the increasingly uninhabitable Sun Belt. Still though, I found this riff from the great Jason W. Moore helpful for approaching the Triple Frontera relationally rather than just by tallying up its material reserves:

“World accumulation, enabled by productivity and plunder, is enabled and secured by geopolitical means. As Luxemburg underscores, the circuit of expanded reproduction is enabled by modern states, using ‘force as a permanent weapon.’ That permanent weapon cuts both ways, illuminating the two axes of modern imperialism: the relation between inter-imperialist rivalry and the subordination of new peoples and places. Great wars have been preceded by the stagnation of the Four Cheaps: labor, food, energy, and raw materials. As the Four Cheaps turned dear, re/production costs rise and profitability declines. Modern empires are a counteracting force. Great wars pivoted on establishing new and expanded flows of Cheap Nature – expanding the Great Frontier – and ensuring privileged access by the eventual victor in struggles for world leadership. Whenever Great Powers found their access to strategic Cheap Natures limited, ferocious and protracted wars ensued.

The Great Frontier has been, in other words, the Westphalian System’s safety-valve. Great waves of geographical expansion, militarized at every turn, enabled the imperialist states to realize new and expanded sources and supplies of the Four Cheaps. Dramatically enlarging the actual and latent reserve armies of labor and places, these movements simultaneously and successively reduced capital’s re/production costs and resolved (for a time) the surplus capital problem. In so doing, they underwrote the restoration and expanded reproduction of capital accumulation. Hence, every great industrialization found its logical and historical precondition in a new imperialism. Such imperialisms worked for capital through various mechanisms but always with one overriding pursuit: appropriating new, expanded and cheaper flows of unpaid work/energy in new geophysical and biological frontiers” (Moore, 2022: 8-9).

And so we have come full circle. America is far from the first to seek an expansion of the Great Frontier into the remote place where Argentina, Paraguay, and Brazil meet. The sudden interest the United States took in the Triple Frontera from the late 20th century up to now is simply a repetition of Great Britain during its own period of hegemonic decline. Francisco Solano López and his proto-developmentalist vision threatened to pull the Southern Cone from the British free-trade orbit in the very moment when Albion was becoming dependent on it as a source of food. Or as Moore would put it Cheap Food, grown in seemingly archaic latifundia but for sale on the capitalist world-market (Korol, 2008: 14-15). Bartolomé Mitre, who led Argentina through the Paraguayan War, was also the founder of a system of oligarchic liberalism in which politics was absolutely monopolized by agrarian elites. This would go unchallenged until the super-exploited masses found an ever-flawed champion in the person of Juan Perón.

Empires depend on plausible deniability. Britain was the financier and chief beneficiary of the Paraguayan holocaust, even if Brazilians and Argentines did the actual killing (Korol, 2008: 15). In a less bloody but equally cynical way, the United States has used the AMIA bombing and its legacy as cover for its imperialist offensive against the Triple Frontera and the Southern Cone writ large. It is to the details of how this happened that we now must turn.

References:

Blinder, Daniel. "El uso político del atentado a la AMIA: Irán y Hezbollah." Revista Intellector-ISSN 1807-1260-[CENEGRI] 7, no. 14 (2011): 01-28.

Borón, Atilio. «¿El Comando Sur en la Argentina?». 28 de marzo de 2012. https://atilioboron.com.ar/el-comando-sur-en-la-argentina/.

Borón, Atilio. América Latina en la geopolítica del imperialismo. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Luxemburg, 2013.

Korol, Claudia. “1.1 TRIPLE FRONTERA: ¿TEATRO DE OPERACIONES DEL IMPERIO O ESPACIO DE ENCUENTRO DE LOS PUEBLOS?” In TRIPLE FRONTERA: RESISTENCIAS POPULARES A LA RECOLONIZACIÓN DEL CONTINENTE, eds. Claudia Korol and Silvia Bignami. Centro de Investigación y Formación de los Movimientos Sociales Latinoamericanos, 2008.

Lazaroff, Tovah. «Netanyahu to French, European Jews after Paris Attacks: Israel Is Your Home». 10 de enero de 2015. https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/netanyahu-to-french-european-jews-after-paris-attacks-israel-is-your-home-387309.

Moore, Jason W. “Imperialism, With and Without Cheap Nature.” Working Papers in World-Ecology, no. 3 (2022).

Porter, Gareth. «Another Neocon Attempt to Frame Iran Falls Apart – Znetwork». 27 de enero de 2008. https://znetwork.org/znetarticle/another-neocon-attempt-to-frame-iran-falls-apart-by-gareth-porter/.

Uddin, Rayhan «Zionist role in 1950s attacks on Iraqi Jews “confirmed” by operative and police report». 19 de junio de 2023. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/iraq-jews-attacks-zionist-role-confirmed-operative-police-report.

Young, Gerardo “Tato.” Código Stiuso. Grupo Planeta Spain, 2015.